9 mins read

Published Feb 12, 2026

From RED III to Australia's GO Scheme: Why Mass Balance Is the Standard in 2026

Modern supply chains are under pressure to prove the origin and sustainability of their materials.

Chain-of-custody systems help businesses do this by tracking materials from source to end product.

Mass balance is one such system: it lets companies mix certified sustainable materials with conventional ones while ensuring that the total amount of certified input matches the claimed output. This way, even if sustainable and conventional inputs are co-processed, the accounting ensures that every claim is backed by actual sustainable purchases.

This approach avoids the need for costly separate supply chains and is already used in key sustainability initiatives. It’s one of several chain-of-custody models, others include segregation and certificate trading, and is a practical, credible way to build more sustainable supply chains at scale.

Why Does Mass Balance Matter?

Mass balance might sound like accounting jargon, but it has real benefits for sustainability, traceability, and business compliance. Here’s why it matters:

Scalability: It allows companies to gradually increase the share of sustainable materials without costly infrastructure changes, accelerating the shift to greener products.

Traceability: Even when materials mix, companies must record every input and output, ensuring transparent supply chains.

Compliance: Many regulations (like the EU RED II) require mass balance for biofuels and other sustainable products.

Efficiency: Companies can integrate greener materials into existing processes, making it easier to decarbonise complex industries.

Credible Claims: When audited and certified, mass balance allows companies to make honest, data-backed sustainability claims, avoiding greenwashing.

In summary, mass balance matters because it makes sustainability feasible at scale. It provides a trustworthy system to integrate greener materials into supply chains that weren’t built for them, all while meeting compliance needs and being transparent about it.

How Does Mass Balance Work in Practice?

The core idea of mass balance application is bookkeeping: for a given factory or supply chain, keep a record of sustainable inputs and make sure you don’t allocate more “sustainable output” than you put in.

Here’s a high-level look at the process:

Mass balance example: Consider a factory that uses a mix of 30% certified sustainable feedstock and 70% conventional feedstock in its production. All the material gets mixed together in the process. Through the mass balance approach, the operator assigns that 30% sustainable portion to the outputs in an equivalent way.

In practice, this could be done in two ways:

They might label every product as 30% sustainable content, or;

They could certify a certain subset of the output as 100% sustainable (up to that same 30% of total volume) and the rest as 0%.

Both approaches reflect the same overall reality – that 30% of the raw materials were sustainable. What they cannot do is claim more than that 30% across the outputs. In our example, after accounting for any process losses, the company could claim, say, 270 kg of product as “100% recycled content” or 540 kg as “50% recycled,” but not magically certify all output as recycled. Even if a particular item off the line contains only conventional material, another item will contain the equivalent sustainable share, such that across the whole production run, the math adds up.

The crucial point is that the total sustainable input equals the total sustainable output claimed. It might be impossible to tell which molecules of plastic in a wrapper came from bio or circular feedstocks, but we know that the manufacturer used, for example, 1 tonne of circular feedstock for every 3 tonnes of plastic they made, so effectively one-third of their production by weight displaced fossil-based material. In other words, the environmental benefit is real, the fossil feedstock was replaced by the sustainable feedstock upstream, even if the mix is homogeneous.

Implementing Mass Balance

To implement mass balance, companies set up internal systems to track materials. Typically, they maintain a mass balance ledger (record) at each site. Every time they receive certified sustainable material, they add it to the ledger; every time they ship out product and want to claim some sustainability attribute, they deduct it.

Conversion factors are applied to account for yields and losses, for instance, if 100 kg of bio-feedstock yields 90 kg of product, they can’t claim more than 90 kg of “bio-based product” from that input. These rules ensure the accounting is honest and conservative.

Critically, independent certification bodies audit these records. A company can’t just self-declare; they are usually part of a certification scheme that lays out the mass balance rules. Auditors will verify that the inputs, outputs, and claims all line up (often checking over a defined period, like quarterly or annually). The process is governed by standard, for example, ISO 22095:2020. It is a chain-of-custody standard that outlines how to do mass balance bookkeeping, and many certification schemes follow similar principles.

Companies also issue or receive ‘proof of sustainability’ declarations with shipments: when sustainable material is transferred between sites or companies, a document travels with it declaring the quantity and characteristics that are sustainable. This paper trail means that if you follow the chain upstream, you can find where and how the sustainable portion originated.

Example of Carbon Central's Proof of Sustainability Documentation.

In summary, mass balance in practice works like a controlled accounting system for sustainability.

Examples of Mass Balance in Action

Mass balance is applied in many sectors. Here are three prominent examples:

Biogas / Renewable Gas

Biogas (or biomethane when purified) is a renewable gas produced from organic waste, and it can be injected into existing natural gas pipelines. The challenge is that once in the grid, the biogas mixes with fossil natural gas. Mass balance principles are used to handle this: gas producers inject a certain volume of biomethane into the network and issue certificates or credits for that amount.

Customers (like a factory or home) at the other end can purchase those credits and claim they used that equivalent volume of renewable gas, even though physically the molecules they burn may be mixed. What matters is that the overall balance is respected – no one claims more green gas than was actually put in. This system, often called a book-and-claim, underpins many Green Gas certification schemes. It ensures renewable energy usage can scale up using the existing gas infrastructure.

For compliance with emissions targets (e.g. in EU climate policies), each unit of biomethane must be tracked. Certification schemes (like ISCC or national biogas registries) certify the sustainability of the biogas and use mass balance accounting to link injections to end-use claims. This way, a city bus fleet can proudly say it runs on renewable gas, given that the equivalent biogas was fed into the grid on their behalf and no one else is claiming it.

Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF)

Aviation is embracing mass balance for bio‑jet fuel. SAF production often blends green hydrogen, bio‑oils or synthetic kerosene with conventional jet fuel. Because the final jet fuel is chemically uniform, the industry uses a book‑and‑claim chain-of-custody. As the IATA guidance notes, book-and-claim allows “organisations to claim and trade the environmental benefits” of SAF via certificates, separate from the physical fuel.

In effect, airlines or fuel blenders can buy SAF credits from certified producers and claim the corresponding fuel as renewable, even if the actual kerosene delivered is a mix. This system ensures that if an airline credits using 100 tons of SAF, then 100 tons of genuine biofuel were produced and entered the market, keeping the carbon accounting accurate.

Book-and-claim provides flexibility – a producer in one location can supply SAF to the market, and an airline anywhere can purchase the environmental attribute, supporting SAF production even where direct logistical supply is limited.

Notably, regulatory compliance like the EU’s ReFuelEU mandate will require physical blending at hubs, but book-and-claim is being used for voluntary markets and international accounting of SAF uptake.

Figure 1: How mass balance enable flexible fuel distribution while maintaining traceability.

Bio-based / Circular Feedstocks (Chemicals & Plastics)

The chemicals industry uses mass balance to incorporate recycled or plant-based inputs into mainstream production. For example, chemical recycling converts plastic waste into pyrolysis oil, which is then fed into an existing petrochemical cracker. BASF’s ChemCycling® program illustrates this: mixed plastic waste is turned into pyrolysis oil and co-processed with naphtha. The resulting polymers are the same as conventional plastics, but BASF claims an equivalent share as “recycled content.”

Similarly, many refineries co-process waste cooking oil or vegetable oil with crude: if 5% of the total feed is bio-oil, they can label 5% of the fuel output as renewable diesel or bio-jet. These mass-balanced bio-attributed products (often certified by ISCC PLUS or equivalent) allow companies to market “X% bio-based content” without any physical segregation. This is vital for meeting regulations (e.g. recycled plastic quotas) and for gradually building a circular raw materials market.

Each example follows the same principle: mix sustainable and conventional inputs, but carefully account for the sustainable share in the final mix. The result is that end users can claim a verified sustainable content with confidence, knowing independent certification has verified the math.

Certifications and Standards: Ensuring Credibility

Because mass balance replaces physical separation with paperwork, robust rules and audits are essential. Key frameworks include:

ISCC (International Sustainability & Carbon Certification)

A leading global scheme covering bio- and circular feedstocks. ISCC PLUS certification lets chemical, fuel and plastics companies use mass balance to validate their recycled or bio-based inputs. Every participant (from feedstock producers to manufacturers) is audited to ensure their input-output accounting is correct.

In practice, ISCC’s criteria define how to calculate yields, losses and allocations so that claims are conservative and consistent. An “ISCC-certified” label gives customers confidence that reported bio-content is backed by this chain-of-custody system.

The ISCC EU scheme is officially recognised under EU law for biofuels, covering the full supply chain from raw material to fuel

EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED III)

RED III is the EU’s updated law (adopted in 2023 as part of the Fit for 55 package) governing renewable energy. It explicitly mandates a mass-balance chain-of-custody for biofuels, biogas, and other renewable fuels.

In effect, any fuel sold as “renewable” in the EU must be traced via an approved mass balance system; unaccounted mixing or double counting is illegal. The directive recognises accredited voluntary schemes (such as ISCC, the Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials (RSB), or REDcert) to implement these rules.

RED III’s requirements for detailed record-keeping, periodic reporting, and independent verification mean that only certified sustainable energy – with proper documentation – counts toward national targets. This legal integration of mass balance ensures integrity in Europe’s green fuel policies and prevents multiple parties claiming the same “green” batch.

Notably, RED III also extends the mass balance system to new areas like renewable hydrogen. For example, the law clarifies that an interconnected gas network can be treated as a single mass balance system for tracking biomethane and hydrogen molecules injected and withdrawn.

Other Schemes (RSB, RSPO, BCI, etc.)

Many commodity standards use mass balance. For example, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) has a Mass Balance model allowing certified and non-certified palm oil to mix in mills, while balancing volumes on paper.

Better Cotton and some forestry/biomaterial standards have similar controlled-blending or credit systems. These sector-specific certifications require the same accountability: audits confirm that the total certified volumes sold do not exceed volumes bought.

In agriculture and forestry, this approach opens markets to more producers (who may not have fully segregated supply chains) while still funneling funds and support to sustainable production. Every link in the chain is checked to ensure that sustainability claims are backed by real inputs and no material is counted twice.

National Guarantee of Origin Scheme (Australia)

Australia’s Guarantee of Origin (GO) scheme officially commenced on 3 November 2025, established under the Future Made in Australia (Guarantee of Origin) Act 2024. It’s a national, government-led framework for emissions accounting and product certification, designed to enhance transparency, support low-carbon exports, and strengthen environmental claims across key industries.

Unlike traditional certification schemes that benchmark against specific sustainability standards, the GO scheme issues digital certificates that document the actual emissions intensity, origin, and production attributes of a product. There are two certificate types:

Product GO (PGO) certificates: These track the emissions and lifecycle data of commodities like hydrogen, green metals, biomethane, and low-carbon liquid fuels. They allow producers and exporters to prove emissions performance and eligibility for Australian incentives (e.g. the $4B Hydrogen Headstart and $6.7B Hydrogen Production Tax Incentive), and help meet international disclosure standards.

Renewable Electricity GO (REGO) certificates: These certify when, where, and how renewable electricity was generated—including from new or existing plants, energy storage, or exported power. REGO will complement and eventually outlive the LRET/LGC system, extending certification beyond 2030.

The Clean Energy Regulator administers the GO scheme, maintaining a national registry, enforcing compliance, and applying the official Measurement Standard 2025 and Methodology Determination 2025. These methodologies align with the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (NGER) system and global emissions accounting practices. Cost recovery began in 2025 under the related Charges Act and Regulations.

Mass balance plays a foundational role in this scheme. For example, hydrogen production from electrolysis is already covered, with mass balance-based emissions tracking matching renewable electricity inputs (via REGO certificates) to certified hydrogen output.

The government has announced plans to expand the Methodology Determination to cover additional priority products, including green metals, low-carbon liquid fuels, and biomethane. In early 2026, the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) will begin public consultations on further scheme amendments to support emissions tracking for biogas and biomethane from anaerobic digestion, renewable diesel, and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) produced via the HEFA process, as well as iron ore mining. These steps reflect the government’s intent to broaden product coverage and align GO certification with international low-emissions trade requirements.

This scheme marks a major policy shift: it embeds product-level emissions accounting into national legislation, enabling credible claims, supporting export market access, and aligning with the EU’s CBAM, RED III, and international disclosure regimes. It positions Australia as a serious player in the global low-carbon product space, with mass balance principles underpinning traceability and integrity.

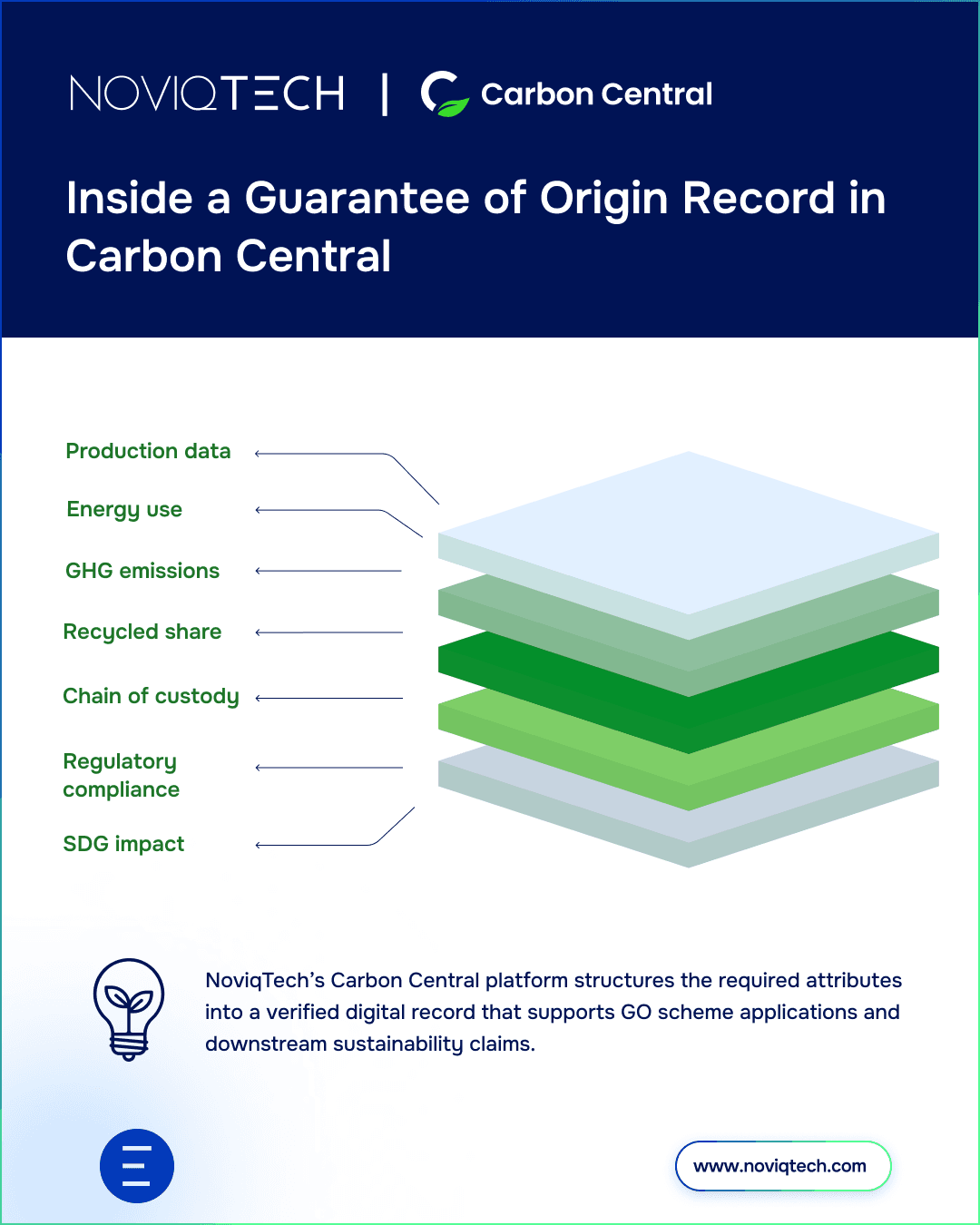

Figure 2: Inside a Guarantee of Origin Sustainability Information Record in Noviqtech's Carbon Central platform.

ISO and International Standards

International standards help codify these models. ISO 22095:2020 (Chain of Custody – General Terminology and Models) explicitly lists mass balance (termed “controlled blending”) as a valid chain-of-custody model, alongside identity preservation, segregation, and certificate trading.

Such standards provide harmonised definitions so that “mass-balance certified” means the same thing worldwide. Regional standards bodies are following suit; for example, European CEN and national standards (like EN 16785 for bio-based content) recognise book-and-claim approaches for calculating recycled or bio-based content. By adhering to globally recognised standards and undergoing third-party audits, companies ensure their mass-balance claims are credible and transparent, minimizing the risk of greenwashing.

Auditors typically check that the bookkeeping is solid – that the total sustainability attributes claimed never exceed the certified inputs, and that appropriate conversion factors and loss rates are applied. These checks, anchored in standards, give stakeholders confidence in the mass balance system.

Conclusion

Mass balance is a practical workhorse of sustainable supply chains. It enables companies to start integrating recycled, renewable, or waste-based materials into complex value chains today, without waiting for a future state of 100% segregated green supply. By carefully matching sustainable input to claimed output on paper, mass balance ensures every “green” claim corresponds to an actual action – a certified sustainable material that was produced and used somewhere in the chain.

This accounting model supports compliance with laws and standards while building trust among stakeholders. For regulators, it provides a clear audit trail (for example, the EU’s forthcoming Union Database will log every batch of sustainable fuel to prevent double counting); for businesses, it offers a scalable, cost-effective path to circularity; for consumers, it signals that environmental claims are backed by real data. In short, mass balance is a key enabler of the circular economy and the renewable energy transition – a transparent bridge from today’s mixed material flows toward a fully sustainable future.

As we move forward, mass balance approaches are likely to become even more common and refined. Sustainability requirements are tightening – the EU’s RED III has come into force with higher targets, and other regions (including Australia and the U.S.) are developing renewable content rules – which will further standardise mass balance methods.

We may see improvements to enhance transparency for consumers (for instance, clearer labeling of “mass-balance content” on products) or deeper integration with digital traceability technologies (such as blockchain or centralised databases for secure record-keeping). But the fundamental concept will remain a powerful enabler for circular economy solutions: by accounting for sustainable material inputs and outputs, mass balance allows industries to credibly transition from fossil-based to renewable and recycled resources at scale.

Curious about how mass balance can work for your business? This approach can be tailored to many supply chains – from energy to manufacturing. By setting up the right internal tracking and obtaining certification, you can start attributing a share of your product to sustainable sources, even within existing production systems. The first step is to assess your material flows and choose a suitable certification scheme or standard to follow.

Our team is here to help navigate the details and put the right systems in place. Reach out – we’re ready to walk you through implementing mass balance and achieving verifiable sustainability claims for your products.