7 mins read

Published Dec 11, 2025

Chain of Custody Models Explained: Identity Preservation, Segregation, Controlled Blending, Mass Balance & Book and Claim

Chain-of-custody (CoC) Models are systems that track materials and their sustainability attributes through every step of a supply chain.

A robust CoC is essential because it underpins any environmental claims a product carries. In other words, due to the complicated nature of various supply chains, it is extremely difficult to verify the sustainable nature of a green product without tracing how it flows through production, distribution and end-use using systems such as CoC.

There are two key elements that are commonly traced across the CoC models:

Physical Material: The actual physical product that is to be produced from raw materials through a supply chain.

Sustainability Attribute: The administrative record of how sustainably the physical material was produced as compared to its non-sustainable counterpart, often supported by a sustainability certification framework.

Different CoC models offer varying levels of traceability and flexibility. Some track the physical flow of materials and its sustainability attributes very closely, while others rely on bookkeeping and certification of sustainability attributes independent of how the physical material flowed through its value chain. It is important to note that adopting a chain-of-custody model requires aligning day-to-day operations with the rules and requirements of that model.

NoviqTech’s Fuel Central platform supports alignment with all major CoC models – including Identity Preservation, Physical Segregation, Controlled Blending, Mass Balance, and Book & Claim – to help businesses meet their sustainability goals. These models are used across industries from plastics recycling to biofuels and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF).

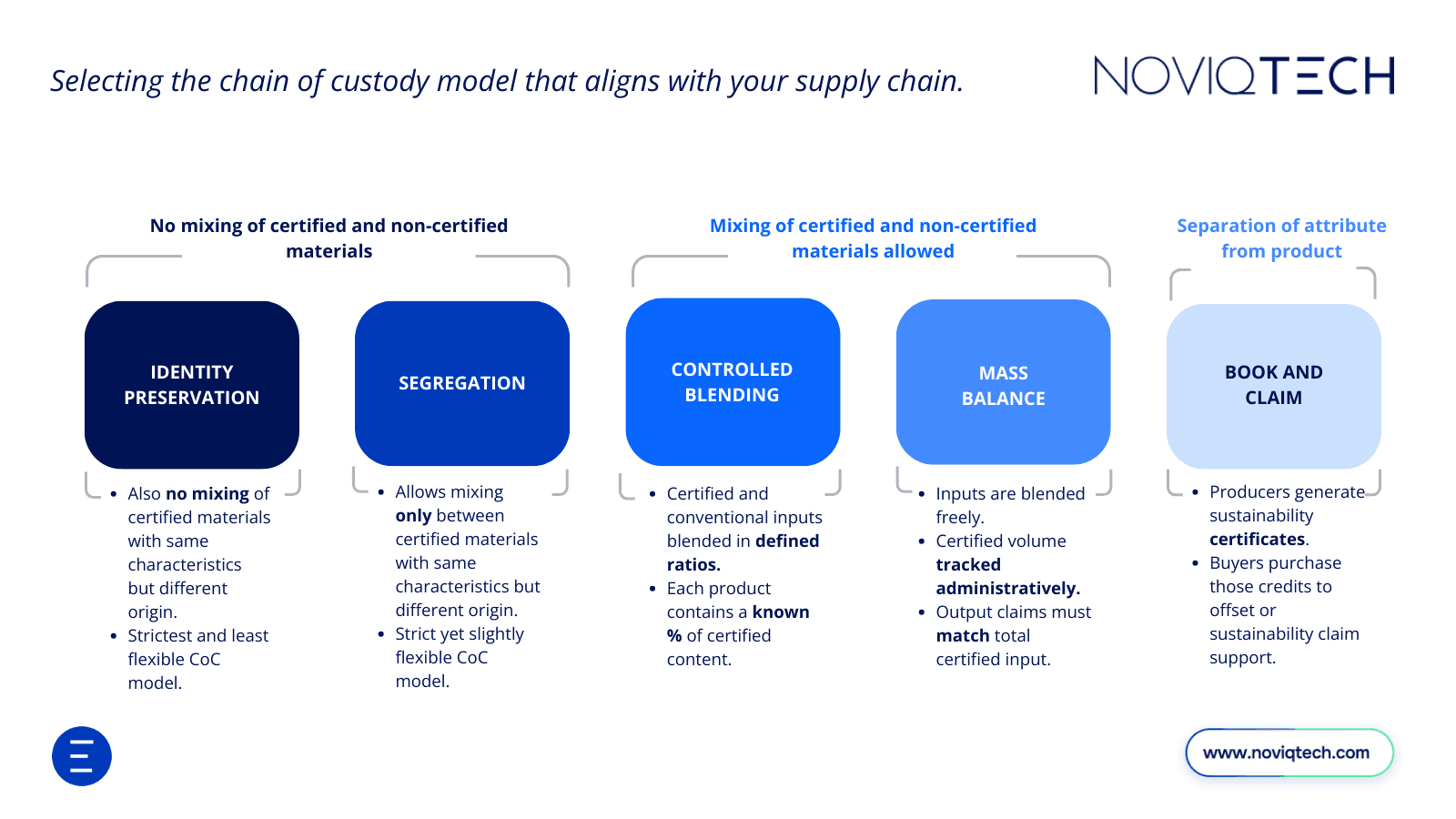

Figure 1: Selecting the chain of custody model that aligns with your supply chain.

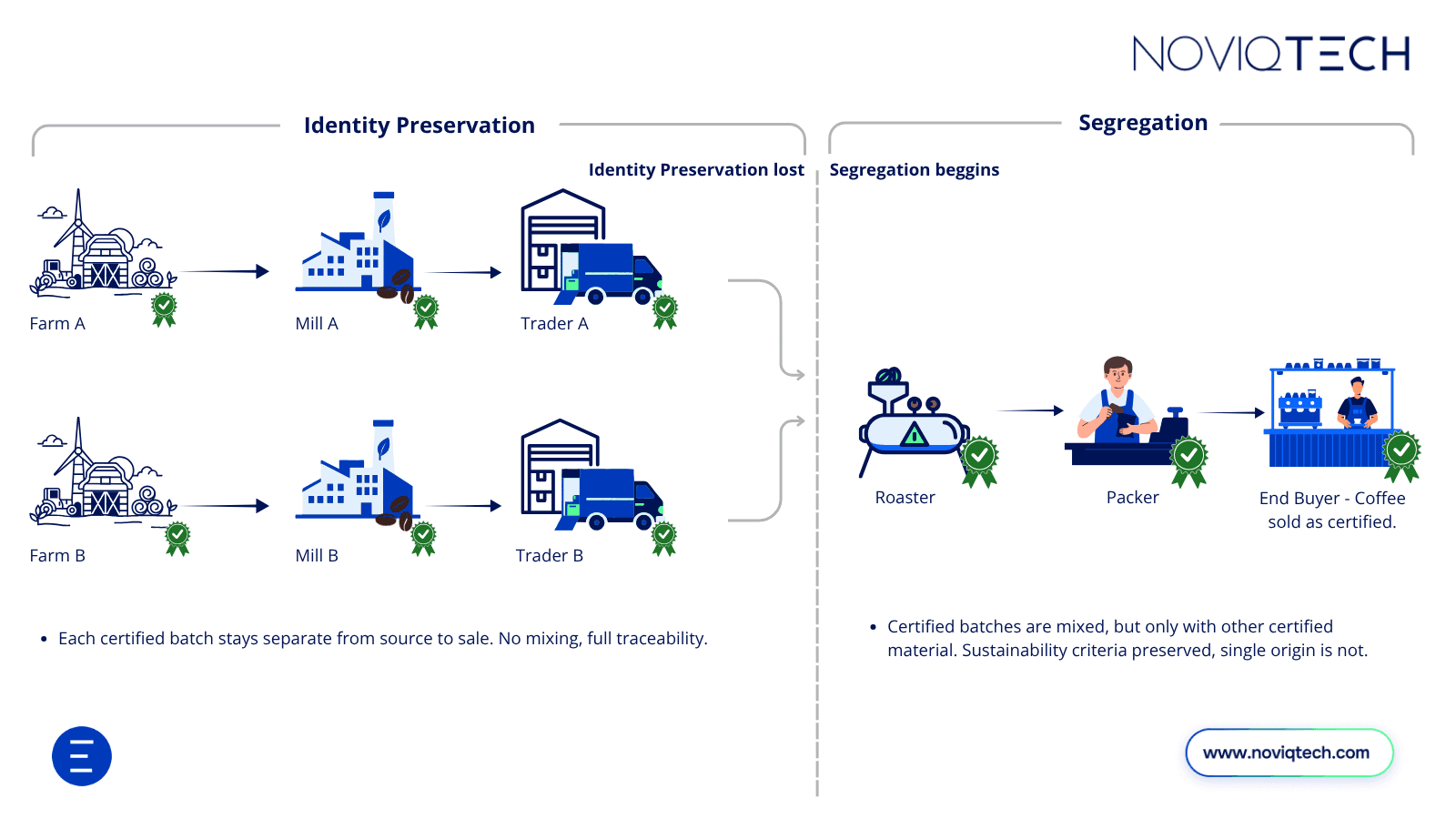

Identity Preservation

In Identity Preservation (IP), each certified batch or lot is kept completely separate and traceable to its unique source. No mixing with any other material is allowed. This means you can say exactly which farm or site supplied the certified feedstock and how exactly was it produced at a batch level. IP is the most stringent model: each batch (lot, tank, shipment, etc.) is handled on its own, with its documentation never combined with other batches.

Key Features: 100% traceability; no physical mixing with other certified or non‑certified material; each lot tracked from origin to final product.

Typical Use: Premium or niche products where provenance is critical (for example, single-origin organic coffee beans or specialty crops).

Example: A company producing an elite biodiesel might use only feedstock from one farm. Under IP, the entire production line is kept separate from all other fuels all the way to the final product. When the fuel is sold, the certificate clearly ties it to the value chain..

By preventing any mixing, IP ensures the highest level of assurance that a product is truly sourced as claimed. However, it is also the most expensive and complex to manage, since it requires separate handling and documentation for every batch. In practice, IP is used when traceability adds real value – for example, gourmet foods, specialty textiles, or certain biotech chemicals. Consumers of single-origin products often willingly pay a premium for this guaranteed traceability.

Segregation

Segregation (SG) is slightly less strict. Under segregation, certified and non-certified materials are never mixed, but you can combine different certified batches together.

Key Features: Certified goods with same sustainability characteristics but from different sources may be pooled together, but at every step the mix contains only certified material Documentation distinguishes certified vs. non-certified flows.

Typical Use: Common in commodity supply chains where complete separation is needed but exact origin is less critical. For instance, any certified sustainable palm oil from different plantations could be stored together as one “segregated” batch.

Example: A biofuel refinery might receive several shipments of certified waste feedstocks from different suppliers. Under Segregation, the refinery can put them all in one certified tank as long as they have the same certified characteristics. It ensures the final product (say, a batch of renewable diesel) contains only certified inputs, although it does not track which input came from which supplier.

Segregation is often called “bulk commodity” or “soft IP.” It offers high confidence that products meet the sustainability standard, while allowing some flexibility in handling. If a mix of certified sources in one batch is acceptable, Segregation cuts costs relative to Identity Preservation. Many certification schemes and standards offer both IP and Segregation as options, depending on how granular the traceability needs to be.

Figure 2: Example showing how certified coffee can be downgraded from identity preservation to segregation. Source: ISEAL Chain of Custody Models and Definitions v2 (2025). Adapted by NoviqTech (2025).

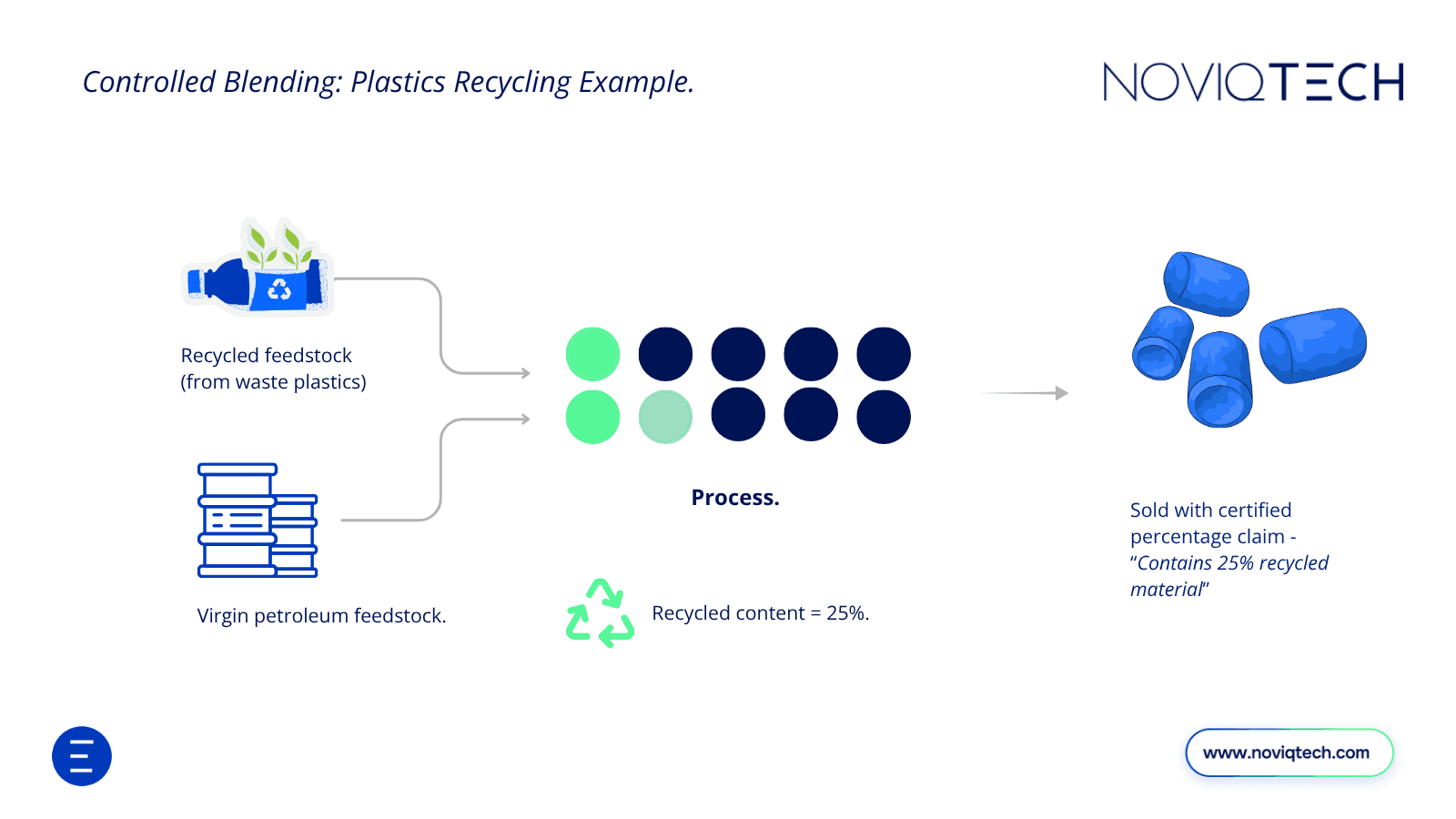

Controlled Blending

Controlled Blending (sometimes called Fixed or Guaranteed Blending) lets you mix certified and non-certified materials in known proportions, and tracks those ratios through production.

Key Features: Certified and non-certified materials are mixed in fixed, documented percentages (e.g. 30% certified, 70% conventional). The ratio is tracked through the supply chain.

Typical Use: Common in textiles (e.g. blending sustainable and conventional cotton) and in fuel blending. It’s useful when manufacturing a product from mixed inputs but still wanting to state a guaranteed share of sustainability content.

Example: A biofuel producer blends certified sustainable feedstock with conventional feedstock at a fixed ratio – say, 25% certified material in every batch. This ensures consistent sustainability performance and allows the producer to market the fuel as “contains 25% certified sustainable feedstock” meeting regulatory and corporate targets.

Figure 3: Controlled Blending: Plastics Recycling Example.

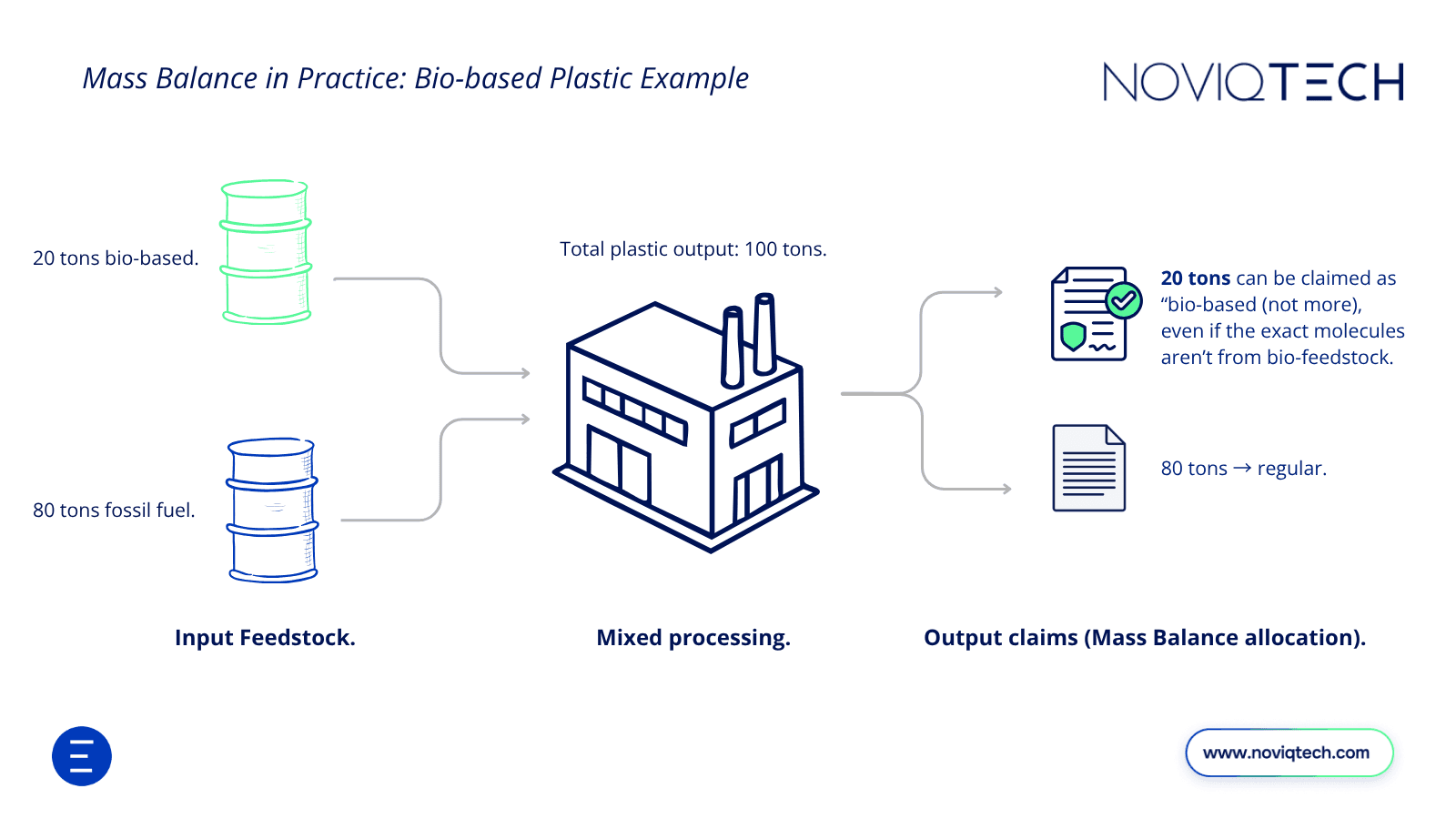

Mass Balance

Mass Balance (MB) is one of the most widespread chain of custody models in industries like energy, chemicals, and agriculture.

Key Features: Mixed physical flow (no requirement to keep certified materials separate). Requires careful input/output reconciliation so that certified outputs ≤ certified inputs over a set period. Usually conversion factors are applied (e.g. to account for processing yields and losses). The sustainability attributes are recorded using mass balance bookkeeping to ensure appropriate allocation of sustainability characteristics to the outputs.

Typical Use: Widely used in chemical, plastics, biofuel, and paper industries where true physical separation is impractical. It enables large-scale recycling or bio-based production using existing infrastructure.

Example: If a plastics plant feeds 20 tons of bio-based feedstock into a process along with 80 tons of fossil feed, they have 20 tons worth of “sustainable credits” to allocate to the output. They might label some portion of their plastic product as bio-based (even those molecules might not be from bio-feedstock) if total labelled output doesn’t exceed 20 tons worth.

Figure 4: Mass Balance in Practice: Bio-based Plastic Example

Book and Claim

Book & Claim is the most decoupled chain-of-custody model, a purely attributional system that breaks the link between the physical flow of goods and the ownership of sustainability attributes.

Key Features: No physical segregation. Sustainability attributes (e.g. GHG reductions, certified content) are fully transferred via an administrative registry or trading platform. The material may be physically sold as non-certified to ensure that sustainable credits do not exceed certified volume of the material to prevent double-counting.

Typical Use: When chain-of-custody is impractical (e.g. infrastructure limits or very low volume supply), book-and-claim enables support for sustainable production. Common in renewable electricity markets (Renewable Energy Certificates) and increasingly in sustainable aviation and shipping fuels.

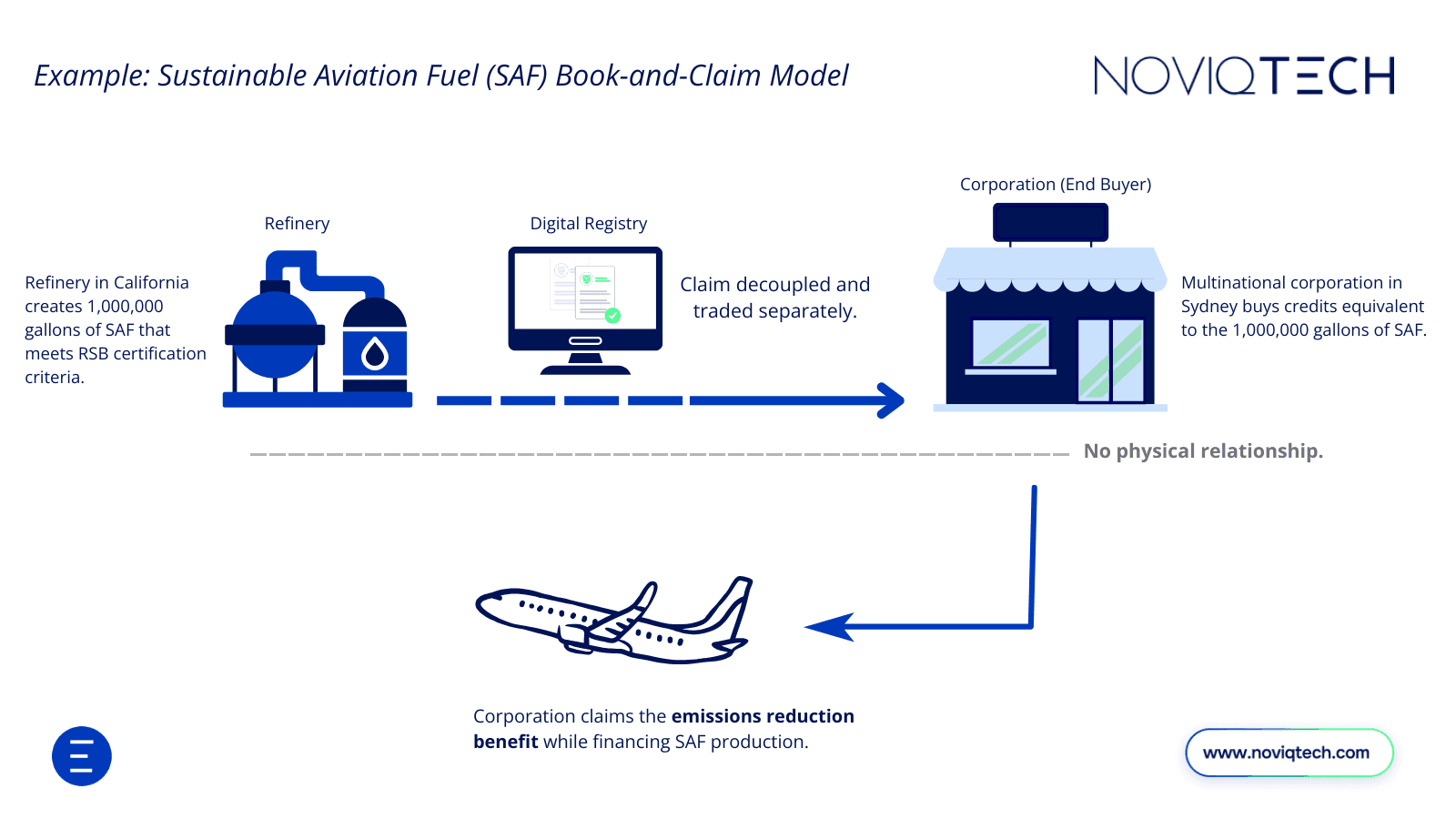

Example: Suppose a sustainable fuel refinery in California produces a batch of SAF that meets all certification criteria (e.g. under the RSB standard). Delivering that SAF to every corporate jet customer around the world would be infeasible. Instead, the refinery injects the SAF into the local fuel supply at LAX airport (where it will displace some fossil jet fuel for flights there). They then issue SAF certificates – say 1 certificate per 1,000 gallons of SAF – into a registry. A multinational corporation in Sydney, wanting to reduce emissions from employee travel, buys those SAF certificates equal to the jet fuel their staff’s flights consumed. The corporation can now claim the emissions reduction as if those flights used SAF. Meanwhile, the physical SAF was used in California on other flights, but the climate benefit is accounted to the corporation that paid for it, and the payment helps the SAF producer. This book-and-claim arrangement is audited to ensure the certificates correspond to real SAF volumes and are only sold once. It’s endorsed by bodies like ICAO and industry groups to channel funds into development of SAF and cut aviation emissions despite the logistical constraints.

Figure 5: Example: Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) Book-and-Claim Model.

Chain of Custody Models Comparison

CoC Model | Mixing Allowed? | Physical Sustainable Content in Product | Example Claim | Typical Use Cases |

Identity Preserved | No mixing at all (every source kept separate. | Yes – 100% from one source (fully traceable). | “100% from [Specific Source]”. | Niche, high-traceability products (single-origin foods, specialty materials). |

Segregated | Mixing of certified sources only; no conventional mixing. | Yes – 100% certified content (from any certified sources). | “100% Certified [Sustainable Material]”. | Common for certified commodities (organic cotton, sustainable palm oil, etc.). |

Controlled Blending | Yes, with conventional but at set ratios. | Yes – each product has a known % sustainable content. | “[X]% Recycled/Sustainable Content”. | Transition phase products (blended plastics, cotton, fuels with partial bio-content). |

Mass Balance | Yes, full mixing with conventional. | Maybe – some products may contain sustainable material, others not, but overall sustainable output matches input. | “Supports sustainable material use (mass balance certified)”. | Large-scale industrial systems (chemicals, fuels, metals) where segregation is impractical; emerging recycling systems. |

Book & Claim | Yes, no physical link needed (credits traded separately). | No guarantee in product (certificate-backed claim only). | “Certificate for X units of sustainable production purchased”. | Renewable energy (RECs), SAF certificates, offset-style programs (when physical supply can’t currently meet demand). |

Table 1: Overview of Chain of Custody Models and their key characteristics and uses.

Choosing a Model

When deciding which CoC model to use, companies consider factors like supply chain complexity, volume of certified material, cost, and sustainability goals. For example:

High-end products or traceability mandates: Identity Preservation or Segregation, because regulators or customers demand full provenance.

Large-scale manufacturing (chemicals, plastics, fuels): Mass Balance is often preferred for efficiency. (It’s the default in many existing certification systems.)

Mixed production lines or partial blends: Controlled Blending lets producers still make accurate claims about the percentage of sustainable content.

Disparate supply or emerging markets: Book & Claim can jump-start demand (as seen in SAF and biofuels) by letting buyers financially support green production.

Ultimately, no single model is “best” for all situations; each has a role.

If you’re ready to implement a chain-of-custody model in your operations, ensure you have the proper tracking systems and certification in place. NoviqTech's Fuel Central specialises in helping companies implement robust chain-of-custody systems. We provide tools and expertise to manage these models seamlessly. Whether you need full-traceability for a premium biofuel, a mass-balance ledger for recycled plastics, or support with Book & Claim certificates for SAF, we can guide you through the process.

Start by evaluating which CoC model fits your operation. Credible sustainability claims start with a solid chain of custody, and we can help you build it. Book a call to get started.